Two days since Daddy and I got back to Tokyo and he told me he’s a spy. One week until school starts. Two weeks until Mama returns from helping Kristin get situated in college in the States.

I’m walking around in a daze.

Whenever a memory comes, any memory, I run it past the new “ . . . and Daddy was a spy” meter and re-assess it. How does the revelation about Daddy affect that particular memory? Does it color or change it in any way? Does it give me a different perspective? Does it raise questions?

The secret is prominent in my mind. I feel shady just thinking about it, as if I’ll also become a spy. Duplicitous. Not telling the whole truth. Pretending.

I will be entering my junior year of high school with a different sense of who I am or why I’m even here. I’ll give a second thought to what my friends’ parents do for a living and what that might really mean. I will pay more attention to conversations I previously considered inconsequential. I will no longer respond to the question, “What does your dad do?” with that same sense of simplicity. Whenever Daddy’s occupation comes up, even in the most casual manner, a mental and physical “alert” will sound internally, reminding me that my answer is now half-truth.

Two afternoons after our return to Tokyo and Daddy’s confession, I’m sitting on the couch in the living room, feet up on the coffee table, reading a book. I hear the faint sounds of drumming in the distance. It’s a rhythmic beat with an accompanying sound of synchronized chanting and clapping. I jump. The Obon Festival!

In the five years we’ve lived in Tokyo, we’ve only been around for the Obon Festival once, because it’s in mid or late August, usually just before we get back from our summer vacation. I call out to Daddy, who is working in the study upstairs, “Daddy! It’s the Obon Festival parade! Do you hear it??”

“Yeah!” he shouts down the stairs to me.

“Wanna come with me and watch?”

“I can’t right now, Joa. Go ahead! Have fun!”

I scramble to put on my shoes and get outside as quickly as possible, running to make my way to the action. In Mejiro, the neighborhood where we live, the festival moves down the main dori, or boulevard, which is about half-a-mile from our house. Taiko drummers (with large traditional Japanese drums draped over their shoulders) are a part of our neighborhood’s parade and their strong rhythmic drum-beating is the sound I hear.

I make it to Mejiro-dori just in time to catch the activity making its way toward me. The taiko drummers wear bandanas on their heads, happi coats (colorful festival attire), obis (Japanese sashes), two-toed shoes, and wristbands. The drumming is very physical and their faces glisten with sweat.

Behind them, I see the large red and gold shrine bobbing up and down. The shrine sits atop a platform made of large horizontal poles. Men wearing traditional summer yukatas (thin cotton kimonos) carry the shrine on their shoulders, bobbing it up and down as they move forward. As they move, they chant loudly to the sound of the drums. Parade attendees gather close to the procession, some nudging their way in to participate in holding the platform for a few minutes.

Everyone on the street claps along and joins the festive chanting as the shrine approaches. I see two adult male gaijin (foreigners) standing together, smiling, clapping, and watching. One of them is talking and pointing to the shrine while the other one listens intently. I detect an English accent and move closer to hear what he’s saying. As I do, he notices me and motions me to come over and be included. I go ahead, even though I don’t know them.

“Do you know what this about?” he shouts over the drums and chanting.

“I actually don’t! Do you?” I respond animatedly.

“I was telling my friend that Obon is a Buddhist holiday marked to commemorate one’s ancestors. It’s their way of celebrating the end of suffering and new beginnings. This is how they celebrate! That portable shrine is called a mikoshi.”

I nod with happy appreciation for this information and we all turn back to watch the bobbing red shrine, or mikoshi, which is now about to pass in front of us. I watch people trying to jump in and participate; it’s not easy to insert yourself as it bobs. It’s crowded under there and the shrine is also moving forward at a good pace.

I catch the eyes of some locals on the other side of the street, pointing to the shrine and motioning for me to go ahead and get under it too. I’m not sure if I should. I’m a gaijin for one thing, and I haven’t noticed anyone my age doing it so far. I respond to their gesture by raising my eyebrows, suggesting that I’m not sure, but they keep pointing enthusiastically. They detect my eagerness. The two adult gaijin men catch this exchange and the English-accented one chimes in. “Get in there! Give it a try!”

I hesitate. The shrine is now almost past us, bobbing above everyone’s heads. Then, in an instant, I make a dash for it. I duck into the throng of pole-holders. It feels like a hot and crowded train in rush hour under there; the men’s backs are drenched in sweat and everyone is squeezed together. (Though unlike the train, everyone is smiling.)

I wriggle my way in, approaching the large pole above my left shoulder. Two men in yukatas nod at me and make room for me to squeeze in. I reach up for the pole; it’s like trying to quickly grab hold of a hand strap as a train car jolts forward. I get a hold of it with my left hand and try to get my shoulder underneath it. Even with all these men holding up the shrine, it is considerably heavy! I join in the loud chanting, adjusting my body movement to stay in rhythm with what feels like a moving organism. I continue for about a minute and then let go, giving way to the continuing thread of new people seeking to replace my spot.

Panting, I disentangle from the moving throng and step out to the watching crowd. I’m a block from where I started. I make my way back and hear the same locals on the sidewalk giving me a big cheer. I oblige them with a little dance of joy, which makes them cheer even louder.

People are dispersing, some following the parade’s tail down the street. The drum beats fade in the distance and I turn to walk home, a big smile on my face. I grab the bottom of my tee shirt, sticking to my back with moisture, and fan it away from my body. I’m reminded of the humidity here. I walk past the neighborhood bath house and then enter our residential block. The drum sound is gone, but the loud cacophony of crickets has replaced it. Ah yes, the distinct sound of Tokyo in the summer.

What a great way to experience my return to Japan. “Now,” my senses tell me. “Capture this,” they beckon. I stop for a few seconds to close my eyes and capture my magnified sensory experience. This moment. The feel of the humidity. The sound of the crickets. My body reverberating from the energy of the parade and the beat of the taiko drums. The sensation of being home. I take a deep breath. Captured.

And then, in a flash, as I walk through the front door, a thought returns to the forefront: “. . . and Daddy’s a spy.”

I enter the house and see Daddy seated in his brown leather chair in the living room, a crystal glass in hand. It’s cocktail hour. Clink, clink goes the ice as he takes a sip. I take off my shoes and walk into the living room, plopping myself on the couch.

“Phew!”

“Fun?” he asks.

“That was great!” I tell him what happened and he beams as I recount my tale. I then tell him what the gaijin man said about the meaning of the holiday.

“Ah. That’s interesting,” he says. “Now we know. New beginnings! I like that.”

New beginnings, indeed.

A few things . . .

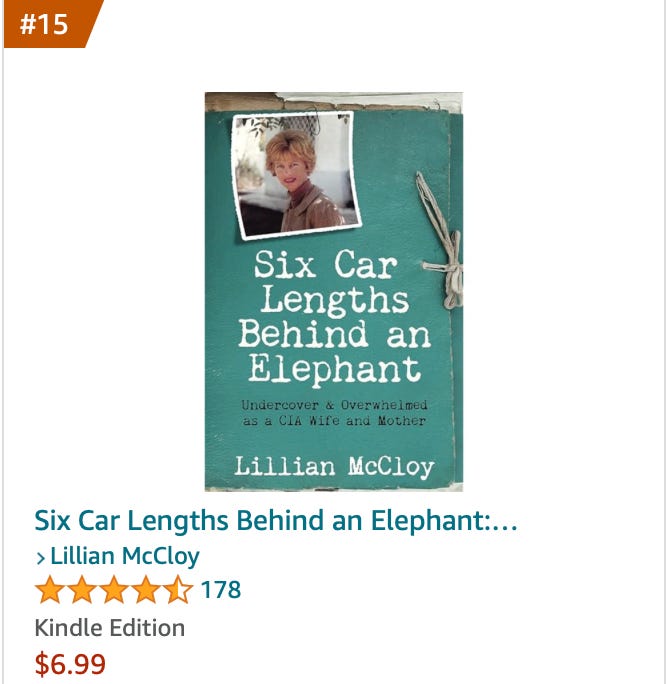

😎 On May 10, my mother’s CIA memoir Six Car Lengths Behind an Elephant was ranked #15 on Amazon’s “Best Biographies of the Cold War.” How cool is that? (If you’re interested in my 30-minute talk/presentation about her life, please contact me.)

👂Would you like to listen to some of my personal stories? I recently recorded voiceovers of three written posts (the ones with personal stories) for the podcast. Listen to them here:

You can find the In This Life Podcast on Substack, Apple Podcasts, and Spotify.

🧏♀️ Do you prefer reading? Or listening? Or both? I welcome your thoughts. (Subscribers: you can also offer feedback in the quick six-question survey.)

Thanks!

Loved this reflection - so many questions! I can relate of course to the split frame of exploring the country you're living in and then the odd realization of "Dad's a spy." So compelling.